For nine sweltering weeks last summer, Ph.D. student Zachary Silvia (M.A. '15) joined an international team of archaeologists excavating the site of an ancient settlement located in modern-day Uzbekistan. The site, known as Bash Tepa, is about a two-hour drive west of urban Bukhara, through the desert, on the edge of the Bukhara Oasis, a once verdant region located along the Silk Road.

If you’ve never heard of Bukhara—or the Bukhara Oasis—you’re not alone. Indeed, for most of the 20th century, western archaeologists were largely denied access to sites in Central Asia due to Cold-War tensions. What little was known came from Soviet Era excavations, published in Russian academic journals. Since 1990, however, access to the region has opened up, making it possible for international teams of archaeologists to set up sites for excavation and discovery.

Zach joined a team led by NYU Professors Sören Stark and Fiona Kidd, and partners from the Uzbekistan Academy of the Sciences. For six previous summers, Professor Stark led excavations on the eastern side of the Oasis, but this past year he shifted his focus to the west, an area with numerous extant archaeological sites. “Bash Tepa is one of about 100 other sites in the region,” Zach explains, “but Bash Tepa is the only site, as far as we can tell, that is fortified, which might bear some significance in terms of the political situation in the region at the time.”

In antiquity, the Bukhara Oasis had a lush landscape, fed by the Zeravshan River, running from a mountain chain in the east. But centuries of aridification caused the river to dry up and turned much of the region into desert.

One of the principle goals of the current excavation is to determine when in antiquity this process of aridification began, which the team plans to do by determining a chronology of settlement in the region. Since this is the first time the site has been subject to a systematic, scientific excavation, they must wait for the results of radiocarbon dating and other tests before publishing their findings. Nevertheless, Zach says that he and the other researchers already have some tentative ideas about when Bash Tepa may have been inhabited. “Based on ceramic finds from this summer, it looks like we have evidence of two periods of occupation, which can roughly be divided into a nomadic, seasonal occupation—probably around 3rd or 4th century CE—as well as an earlier, possibly Hellenistic period of settlement.”

The hypothesis about a period of nomadic occupation is based on evidence that Zach and other members found for the existence of pit houses, a type of domestic structure that was built into an earlier phase mud-brick platform. Nomads might have taken up residence in these semi-subsurface structures, on which they would have built temporary shelters.

The team also found imitation Hellenistic pottery at the site, suggesting an earlier settlement engaged in trade with the Hellenic world. During the reign of Alexander the Great, the Greeks conquered as far east as modern eastern Afghanistan. Subsequent Greek-speaking rulers in the region briefly presided over parts of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, a region once known as Sogdiana.

But Zach is cautious about placing too much importance on the evidence of Hellenistic pottery found at Bash Tepa. “There's been a longstanding tendency to emphasize evidence of contact with the West. In doing so, scholars reveal and perpetuate a bias toward the Greek world. The whole paradigm needs to be flipped on its head.” Understanding how ancient societies interacted with a wider world is important, but Zach is part of a growing group of archaeologists who want to look at Central Asia as a complex region with its own histories, trade networks, indigenous traditions, customs and material culture.

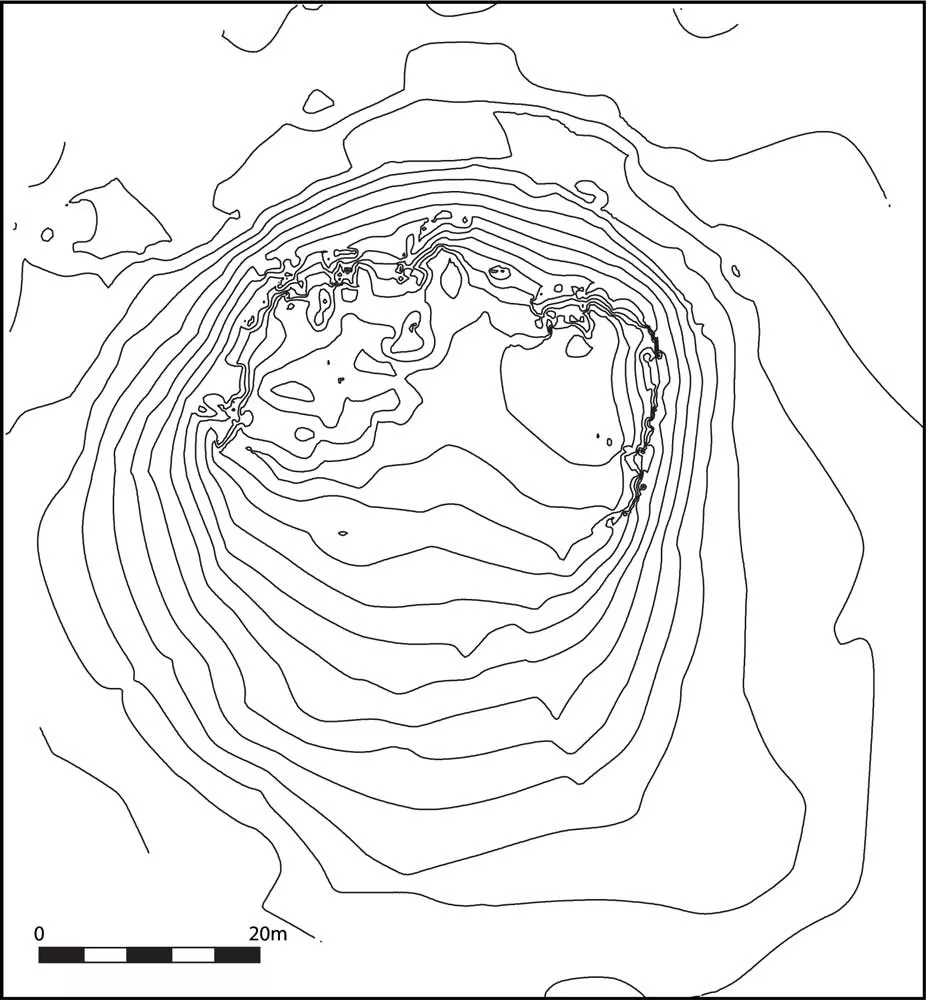

Besides overseeing three trenches at the site, Zach served as site topographer, which allowed him to create a new contour map of Bash Tepa. For decades, scholars have relied on a rather provisional map of the site, created in the 1930s by a Soviet archaeologist under duress. During the Stalinist era, Vassili Shishkin found himself in conflict with the Russian state and a target of Stalin’s proscriptions. He fled into the Bukhara Oasis, where he passed his time making crude maps and trial excavations of many sites in the region. He would later become the famed discoverer of the medieval site of Varaksha, once the largest city in the Bukhara Oasis.

Upon his arrival at Bash Tepa, Zach used Bryn Mawr’s Leica Total Station to map the site with over 2,000 plot points, which he then used to create a new topographic contour map of the site for publication. Zach also was responsible for all of the mapping of the site’s archaeological features.

The team hopes to publish an interim report of their work thus far—including Zach’s maps—before returning to the site next summer. And they have plans to continue at Bash Tepa another season after that, with the possibility of more sites in the surrounding region to follow. Despite the many challenges that remain for archaeologists working in this region—such as geopolitical and language barriers—Zach is committed to continuing his focus on Central Asian archaeology, and to being part of, as he says, “the conversation that explores Central Asian archaeology within its own regional context.”