As I stepped off the tram in a run-down and industrial part of town, I wasn’t sure what to expect. I had just travelled about 15 hours from New York to Germany to see the international art exhibition documenta (with no capitals), which takes over the small city of Kassel once every five years. I didn’t really know what I was getting into either: The organizers released almost no information about the chosen artists or the overall conception, and documenta’s short duration (only 100 days) meant that there were few photographs or reviews online.

I went to documenta because I wanted to see what the curatorial team, led by Adam Szymczyk, felt was the most important artwork of today. Who is the new avant garde? In previous iterations, major artists, movements, and even genres have begun at documenta. However, the curators this year selected few familiar names, focusing instead on artists typically overlooked by the art world’s implicit and explicit racism, classism, and misogyny. This documenta wasn’t about pushing the art world forwards; it was trying to change it altogether. Throughout, there was a persistent desire to select artists from the margins of the art world, including recent immigrants from developing countries, as well as displaced indigenous peoples from Europe and North America. Indeed, migration often featured as a subject of the works themselves.

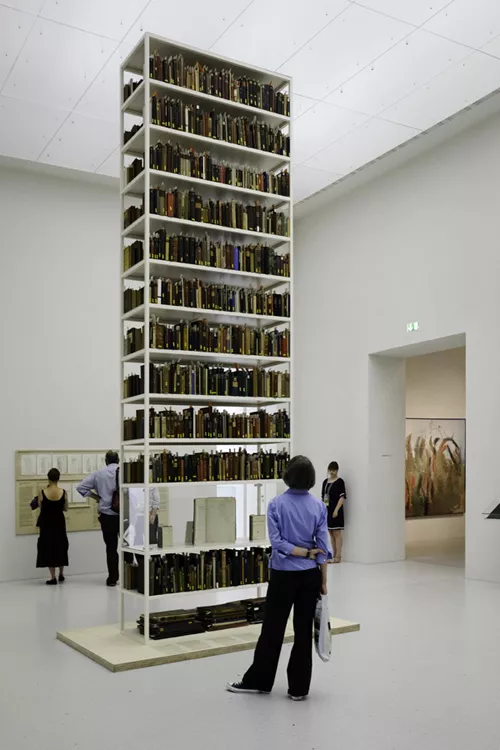

As a whole however, the exhibition lacked accessible and educational interpretive materials, which meant many works were difficult to make sense of. A tour guide told me that the lack of interpretation was intentional: the notion of narrative itself is subjective and shouldn’t be dictated by a label. But, this ironclad belief in open interpretations and multifarious narratives seemed self-defeating. Even as an informed viewer, I at times felt alienated rather than enlightened. I found myself wondering: what is the point of a progressive curatorial strategy if it does not also aim to be approachable to everyone? Many of the works, particularly those dealing with specific archives or global political conflicts, clearly engaged in a narrative history that wasn’t always overt and remained unexplained. The lack of interpretation overall raised questions around how much context is necessary to understand works of art that deal with far-reaching issues. Through such refusals, documenta questioned whether information or context was a useful device towards global empathy.

Overall, I observed both artists and curators turning towards the world and its problems, trying to disseminate facts and history, and moving beyond purely artistic and aesthetic aims. The video works were the most successful in this regard. Angela Melitopoulos’ four-channel film Crossings engaged with a wide range of issues from refugees to environmental destruction at the hands of cooperate mining operations. Ben Russell’s haunting yet beautiful video installation similarly looked at the dark side of mining operations in Serbia and Suriname, highlighting differences in technology, safety, and labor. Coming from a place where the phrase “alternative facts” and questions about truth are at the forefront of the news cycle, I found this turn towards more politically engaged art invigorating and hopeful. I wondered if more art museums might take a page from documenta’s approach, and take a more active role in politics by speaking truth-to-power and giving otherwise marginalized voices a platform. I am hopeful that this year’s iterations contribute to a global conversation about the role of art in this socially and politically charged time.