Archaeology's Christina Chandler Draws Out New Details about Ancient Persepolis

For the past four summers, Christina Chandler, a graduate student in the Archaeology department, has been spending her days in a darkened lab in the basement of the Oriental Institute on the campus of the University of Chicago. She has been painstakingly drawing individual seal impressions from an archive of approximately 20,000 clay tablets housed at the Institute since the mid-1930s. The process—which utilizes photography and computer software—cannot be automated; it requires the patient and careful transcription of individual markings by a human operator, working from as many extant versions of the impression as can be found, to produce an accurate record of the original seal.

The clay tablets from which Christina is working date to the reign of Darius the Great, king of the Persian Empire from the late 6th to early 5th centuries BCE. In the 1930s, a team excavating the ancient city of Persepolis found the archive of tablets in a fortification wall. The tablets contain information about the storage and distribution of food in the ancient city, with each individual tablet serving as a receipt of rations given to people working in the empire. Since rations were given to so many people—members of the royal family, workers, slaves/servants, people traveling, even animals and deities—the administrators required a means of keeping clear records about who was getting food and in what quantities. Indeed, as Christina explains, “writing and sealing practices are coming out of the need to document and administer rations in burgeoning agricultural societies.” To acknowledge receipt of your ration, you would “sign off” with your seal.

Christina is working with a larger team of international scholars who make up the Persepolis Fortification Archive Project, directed by Matthew Stolper. She and others are attempting to document and record as many unique seals as they are able from the archive so that they may be catalogued for future research. But the project poses particular challenges. “The impressions are not always as clear as we would like. Sometimes there is a lot of noise distorting the impression. The goal is to get as much information and to recreate the original seal as closely as possible, which means we sometimes compare multiple impressions made by the same seal in order to get the most accurate representation. There are some tablets with cracks or portions missing, forcing us to omit that information until, perhaps at a later date, we find another impression from which to complete the drawing.”

For researchers looking at this archive, the texts and seal impressions promise to reveal new information about the Persian Empire—details about its economic and administrative operations, class and gender politics, and, of course, further evidence of its robust visual culture. From the text recorded on the tablets, scholars have noticed that, for example, one’s gender, age, and occupation could dictate the size of one’s ration. They’ve also discovered tablets with seals from members of the royal family, designating receipt of an amount of food far greater than a typical ration, suggesting that these individuals were collecting supplies for the royal table.

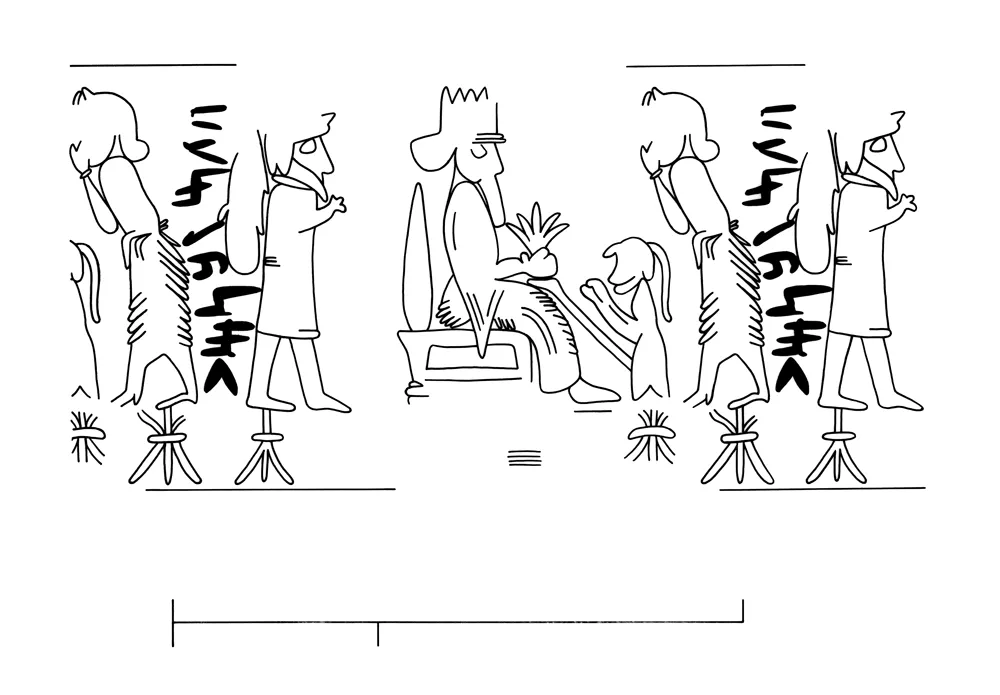

Christina points out that the iconography of the seals can also reveal important distinctions about social standing and Persian visual culture. “The tablets are more than just receipts,” she says, “they offer details about the individuals giving or receiving the rations. For example, there seems to be a relationship between one’s socio-administrative rank and the style and iconography they would have had access to for their seals. Members of elevated rank could use seals that incorporated motifs similar to those used by the King in his monumental art.” A popular scene found on court-centric seals features royally-clad heroes engaging with real or fantastical beasts. By linking these motifs to other archaeological finds in the empire, the researchers are able to demonstrate communication between various workshops and the translation of popular themes across media.

For her dissertation, Christina is examining a group of about 160 seals that combine iconography and text. She is interested in further exploring issues of social stratification and visual culture. While these ancient seals and documents were an important part of life in ancient civilizations, they are rarely seen by contemporary audiences. “In a sense, it’s our job to figure out how to communicate their meaning to people who would normally never see them—they are housed in storerooms rather than on display in museums, and since they often appear in fragmentary form, they are difficult to see and make sense of. Sometimes that requires an art historical approach, sometimes we have to go back and see how and where it was excavated, or how it relates to other Achaemenid period evidence. We have to look at this archive as one artifact—it’s not just a single seal or a text.”

To illustrate her argument, Christina will be able to rely on the work she and others have done to make legible so many of these ancient seals. Indeed, at the upcoming Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America, she will be presenting research on PFUTS 305*, a seal that she studied for her M.A. thesis, which has just been inked and readied for publication.

Christina’s work for the Persepolis Fortification Archive Project is supported by a grant from the Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute.