Bryn Mawr’s liberal arts focus and small classes create the perfect environment for mentorship to flourish. In one chemistry lab, Ben Williams, Ph.D. ’15 has been like “the older brother” who shows undergraduate researchers the ropes.

About five years ago, Meredith Skiba ’12 arrived on the Bryn Mawr campus as a transfer student who was, as she recalls “very gung ho” about majoring in pre-med. Then she signed on for a summer research project where she had an opportunity to work closely with a graduate student named Ben Williams (Ph.D. ’15). It proved to be a life-altering experience.

Her work in the lab with Williams under chemistry professor Sharon Burgmayer, running a series of biological tests on enzymes, led her to a revelation: “Oh, I really like research.” Soon, her plans for medical school were scrapped, and Skiba is now in her third year earning a Ph.D. in biological chemistry at the University of Michigan. And she still stays in touch with Williams to answer questions about ongoing research.

“They were real mentors to us, but they were also friends,” Skiba said, recalling her undergraduate days in the Bryn Mawr chemistry lab with Williams and several other grad students who coached her. “It was really a nice atmosphere to work in. It was like the older brother in the lab.”

Both Williams and Skiba have reaped the benefits of a process that is now getting more attention on college campuses: mentoring. Only in recent years have education experts more closely scrutinized these unique peer relationships to better understand how they can improve student performance and influence career choices, while also helping the mentors become tomorrow’s engaged teachers. A 2011 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that one-on-one coaching increases college graduation rates by 4 percentage points.

The liberal arts focus and smaller class sizes on the Bryn Mawr campus make it an ideal environment for graduate students to mentor and collaborate with undergrads on academic research, especially on lab work in chemistry and physics.

“In a big university laboratory, the emphasis is on getting research done and not providing an important experience for the undergraduate—they just happen to be folks that come in,” says Burgmayer, who is also dean of graduate studies. “Whereas clearly at Bryn Mawr, it’s a liberal arts school and the focus is on undergraduates.” She said the 16 grad students in the two science fields work intensively on collaboration and coaching in the lab.

Williams, on track to receive his Ph.D. in chemistry this spring, has mentored about 10 undergraduate students since he arrived at Bryn Mawr in 2009. Even though he came from another liberal arts school, Franklin and Marshall College, Williams is impressed with the enthusiasm of Bryn Mawr’s undergrads after Burgmayer encouraged collaborating with them on his research.

“Bryn Mawr undergrads are really driven and motivated,” he said. Williams is involved in two research projects: one studying molybdenum enzymes, and the other observing how ruthenium-containing molecules interact with DNA, the building block of human cells. In the long run, he says the ruthenium project could have significant anti-cancer implications, by developing processes that would allow these enzymes to target diseased cells while leaving healthy ones unharmed.

Mentoring is an added learning tool for the graduate student, especially since many of them plan on careers in academia. Burgmayer notes that coaching in the lab builds on their work as teaching assistants, because “they’re not teaching in a lecture sense, but in a very hands-on sense.”

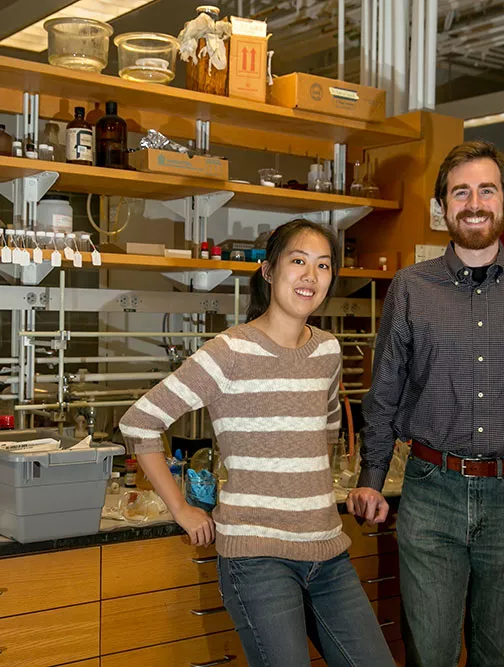

Another student Williams mentored—21-year-old chemistry major Stephanie Yang ’15 —began working with him during her sophomore year. While her research adviser—Burgmayer—was often tied up with her other duties, Yang says it was great to work with “someone older, who’s had experience and who can show me what needs to be done.”

Two years later, she’s working with Williams on the ruthenium research and has traveled with him to Dallas to an American Chemical Society conference to show off some of their results. “It’s just a very nice atmosphere,” Yang says of the lab. “I‘m not afraid to ask questions. Even if they seem kind of silly, he doesn’t discount me.”

As an undergrad, Skiba was thrilled to be credited as a co-author with Williams and another Bryn Mawr graduate student when their research paper was published in a scientific journal. Now, in Ann Arbor, she says that experience is making her a better mentor to younger students there.

“This year I got my own undergrad working at Michigan,” Skiba says, adding that the student is “doing really hands-on work. I set it up like that—I learned from Ben how to do that.”