Du Bois at Bryn Mawr

By any measure, the intellectual and social legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois is extraordinary.

A towering figure in American history, W.E.B. Du Bois was a scholar, a historian, an early practitioner of scientific sociology, an editor, a novelist and poet, a civil rights activist, and a leading male voice in the African American community of his day.

He was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. His pioneering 1899 study, The Philadelphia Negro, was one of the earliest examples of a data-driven social science, based on meticulously gathered statistics. He was among the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and served as founding editor of The Crisis, its monthly magazine. His seminal work, The Souls of Black Folk, remains a touchstone in American literature and a beacon in the fight for civil rights that introduced what might be his most famous words: “The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line.”

He championed full civil rights and political representation for African Americans and campaigned against lynching, Jim Crow, and discrimination. He was also a proponent of Pan-Africanism, a vocal supporter of women’s rights, and an anti-war activist. And as one of the era’s leading intellectuals, he was an accomplished public speaker who lectured throughout the country, around the globe—and at Bryn Mawr College.

And when a call went out to explore the forgotten histories of Bryn Mawr, Vanessa Davies, the associate director of institutional grants at Bryn Mawr, set to work. What she found has formed the basis for a presentation she and Alumnae Association Director Millie Bond ’05 made at Reunion 2019. In addition, Davies recently received support from the College to work with a Library and Information Technology Services team in the creation of a website devoted to the story.

Director of the Alumnae Association Millie Bond '05 (left) with Associate Director of Institutional Grants Vanessa Davies.

In the meantime, the Bulletin sat down with Davies and Bond to talk about an important moment in Bryn Mawr history.

How did you start researching this?

Vanessa Davies: When the call came out for the Community Day of Learning, I had been thinking about Du Bois in the ’20s and ’30s and ’40s—he was everywhere. So I wondered, did he have a connection to Bryn Mawr? And within five minutes of research, I found out, yes, Du Bois was on campus in 1931.

Millie Bond: It was this forgotten piece of our institutional history that no one knew about. We talked to people in the Special Collections, and they weren’t aware that this had happened.

Before we go on, can you explain the Community Day of Learning?

Bond: Every year, the College dedicates a day where the campus community gathers to consider a specific theme. The President’s office puts out a call, and anyone—students, faculty, staff—can propose a session on a topic related to that year’s theme. One of last year’s themes was Engaging Bryn Mawr’s Histories, and when Vanessa saw the call, she set out to find what she could about Du Bois. And that idea of Engaging Bryn Mawr’s Histories is a reflection of a larger effort the College is making to do a better job of telling the history of the institution from various viewpoints—the hidden histories, the untold stories.

So back to Du Bois and Bryn Mawr?

Davies: First, some stage-setting is in order. You have to go back to April 1924 and The Intercollegiate Conference on Negro-White Relationships, which took place in the town of Swarthmore. It was a three-day event, over a weekend—student-run, student-managed—with the stated purpose “to bring together white and black students in the hope that they would understand each other’s difficulties.” It was organized by the Polity Club at Swarthmore, by the University of Pennsylvania Forum—an interracial group—and by Bryn Mawr’s Liberal Club. Attendees came from Bryn Mawr, Haverford, Swarthmore, and Penn, as well as from Penn State, City College of New York (CCNY), Union Theological Seminary, and several what we would now call historically black colleges and universities: Hampton, Lincoln, Virginia State, and West Virginia State. Each college sent two delegates; those that were interracial sent one white and one black student.

What do we know about how the weekend unfolded?

Davies: It was a very intellectual undertaking—readings were assigned prior to the conference, and students were asked to be prepared to talk about specific topics. Each day had its own agenda. The first day looked at the historical background and present-day status of blacks in the U.S. as well as the theory of racial superiority. Day two was devoted to the question, “Is racial discrimination warranted economically, legally, socially?” And day three took on the issue of amalgamation or segregation.

On the social side, afternoons and evenings were left free for walks around the countryside. For the Saturday evening entertainment, every delegation staged a performance—music, dancing, whatever—and the event wrapped up with everyone singing Swarthmore’s alma mater. It’s interesting to think about what students were experiencing on an intellectual level, on a social level—interacting with one another, hearing about one another’s experiences. Particularly for the black students traveling from Virginia and West Virginia, you have to wonder what those trips were like. How did they pay for their travel? What did they think when they arrived at Swarthmore? Where did they stay? Would there have been a problem housing on campus or in town?

We do get a clue about some of those questions from a piece in The Crisis written by Eugene Corbie, a Trinidadian student at CCNY, who wrote: “The Southern delegates gave expression to what they themselves had just undergone in order to attend the conference in the matter of Jim-Crow cars and other public places of accommodation.”

Was there any other after-the-fact reporting on the conference?

Davies: We have write-ups from The College News and Swarthmore’s Phoenix. And this, again from Corbie: “This meeting was full of promise. It made two matters most clear. First that thinking white students are showing a willingness to come to close grips with the problem of color, but that only a very few of them have any comprehensive, scientific knowledge of (people of color), for they are still vastly influenced by tradition and custom. Secondly that every student (of color) must train himself to meet just such occasions as this. For he must be able at any time and place to discuss his case in the light of historical facts and scientific truths.”

Deirdre O’Shea ’26, in a letter to The College News, had a slightly different take. Although offering that the conference didn’t “accomplish” anything, she did see an important opening: “White men and women talked with black men and women about an interactive problem. … a step forward was made—not perhaps in the great national and international question of black and white, but in the segment of it that is ours. And each segment so treated again and again will eventually make one big step.” So that’s April 1924.

What happened in 1931?

Davies: Again, some background. In October 1930, a report titled A Study of the Economic Status of the Negro was released. The product of a commission established by President Hoover, it generated a fair of amount of controversy—not least from Du Bois, who criticized its findings in The Crisis.

Then in January 1931, Annamae Virginia Grant ’33, the president of Bryn Mawr’s Liberal Club, the same student group that co-organized the 1924 conference, wrote to Du Bois, inviting him to speak at a February conference called The Economic Status of the American Negro. Du Bois sent his regrets; he would be out of the country in February. But a month later, when Grant extended another invitation to the rescheduled conference—now slated for April—he accepted.

This was a one-day conference, held in the Music Room in Goodhart Hall. The speakers were big names, and they focused on the inequality of opportunity for people of color in just about every realm: education, industry, politics, standards of living. The morning session was devoted to economics and featured Walter White, the secretary of the NAACP; Alain Locke, a philosophy professor at Howard University; and Ira Reid, the research director of the National Urban League. In the afternoon, Alice Dunbar Nelson and A. Philip Randolph—from the Interracial Committee of the Society of Friends and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, respectively—spoke about labor issues. In the evening session, J. B. Mathews, the only white speaker on the docket, preceded Du Bois on the topic “The Future of the American Negro.”

It's seven years later so, clearly, a different group of Bryn Mawr students are attending. Who else was there?

Bond: So, students come from Swarthmore, Haverford, and Howard, plus from Cheney, Vassar, Johns Hopkins, and George Washington. At least one Penn faculty member, one Bryn Mawr professor, and one graduate fellow were there. The College News reports that a number of college maids attended. From the beginning and well into the 20th century, the College employed maids and porters, most of them African American. There’s nothing more—nothing about how they participated, what they may have thought—just that “a number of college maids came.” But, again, it’s interesting to think about their experience.

Do we know what Du Bois said?

Davies: The College News summarized what all the speakers said. And as for Du Bois, the paper noted his linking of social justice to economic justice: “The real problem of the future is how readjustment is to be brought about with least cost.…There is a danger that these laboring classes (of people of color and people who are not of color) may some day not be stupid enough to ignore their similarity of interest.” He was, the News reported, hopeful about socialism and critical of capitalism. “In the best of times”—this was in the early years of the Great Depression—“Fifth Avenue shops sell merchandise at fabulous prices while dark-skinned colonials work for 20 cents a day.… Social justice cannot be procured without cost to capitalists.”

Bond: And he doesn't spare Bryn Mawr! The College News reports, “Colleges like Bryn Mawr, ‘institutions for handing down every mistake that the older generation has made,’ once in a while as a concession to radicals allow students to think for themselves. Members of the faculty, however, must behave or lose their jobs. Radical students may not be expelled but they are not popular.”

Davies: The article in The College News closes on an inspirational, and prescient, note: "There is a chance for magnificent sacrifice in the cause of racial equality, one of the finest causes the world has ever seen."

Do we have a sense of the response on campus?

Davies: While The College News gave the conference a prime, front-page position with a lot of coverage across two issues, the report also describes it as "a splendid conference poorly attended," with fewer than a dozen Bryn Mawr students present at any given time. Du Bois, on the other hand, clearly saw the conference as noteworthy. He wrote up a tiny blurb about it a few months later in The Crisis, and he mentions the conference and several of the speakers. Plus, he notes that the conferees all ate in the College dining room—a detail that was obviously very significant to him and to his readers.

What happens next with this story?

Davies: The project has been awarded one of the Digital Bryn Mawr Seed Grants, administered by the Library and Information Technology Services department, to support more research and the creation of a website. Right now, we’re in the planning stage and hope to launch by summer’s end.

Bond: This is a very exciting piece of College history that no one seemingly knows about, and obviously there’s more work to be done about these events.

But we don't want to stop here. What are the other forgotten histories of Bryn Mawr? When we presented the Du Bois story at Reunion, we threw this question out to alumnae/i, and the list of names they gave us was impressive: Jane Addams, Coretta Scott King, Martin Luther King, Jr., Dick Gregory, Kate Millett, Nina Simone, Sonia Sanchez, Andrea Gibson, Whitney Young, Ani diFranco, Angela Davis, Gabriel García Márquez.…So we're asking alumnae/i to share what they know—their own memories from their time on campus or stories they've heard from other Mawrters.

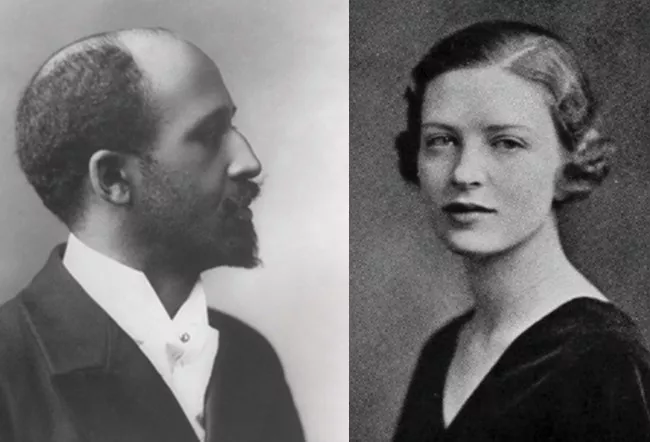

W.E.B. Du Bois and Annamae Virginia Grant '33, president of Bryn Mawr's Liberal Club.

Deirdre O'Shea '26 said of the 1924 conference, "A step forward was made."

Published on: 02/01/2020